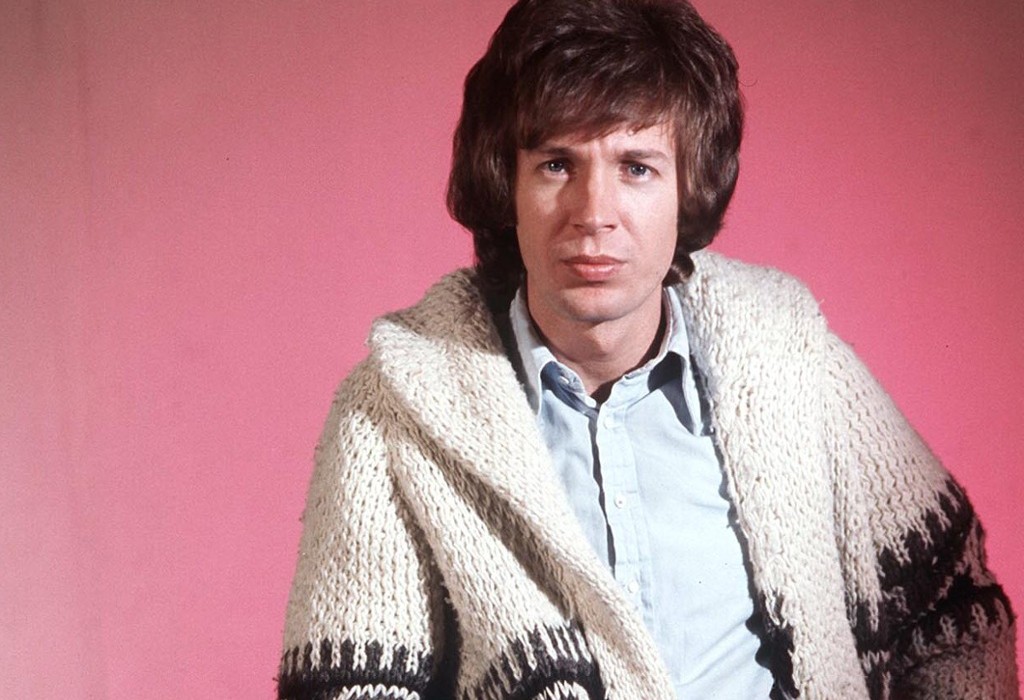

Early in 1966, a group of Americans under the adopted surname of Walker released a cover of a Frankie Valli song and hit the charts as The Walker Brothers. That song is “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore,” and the singer is Scott Walker. The rumor is—on the strength of that one song alone—The Walker Brothers’ fan club was said to have been larger than the Beatle’s in 1966.

Not long after this, Scott Walker would go on to have a successful solo career, for a while that is. He released Scott the year after his initial success with the Walker Brothers, which was a continuation of his work with the Brothers. The notable turn was how dark some of the material had gotten; songs originally by Jacques Brel translated into English by Mort Shuman are Baudelaire set to music. “Mathilde,” the title woman of the opening track gives him woe upon her return, and he laments in “My Death” the passing time, unresting death.

Nineteen Sixty-Eight’s Scott 2 followed the format, again bolstered by Shuman’s translations of Brel’s songs. But it was 1969’s Scott 3 that would set him apart as Scott Walker, songwriter; only three songs on the album were by Brel/Shuman, and they were hunched together at the end, thrown on top like filler. All three albums were a huge success, but the bottom fell out when Scott 4, his most ambitious album to date, failed to chart. He was forced back to recording standards to fulfill a contract, and while Scott 1-4 have all been reissued, he refuses to let these albums see the light of day.

The Walker Brothers reunited in 1975, reviving some of the interest in his career, and the album Nite Flights saw his first new material in eight years, beginning a trend of long intervals between releases. In fact, it wasn’t until 1984 that he released his next album, Climate of Hunter, which saw him dive off the deep end of pop. After another eleven years, Walker released Tilt; avant-garde, experimental, plain weird, and brilliant. Eleven years more, and Walker releases The Drift, the kind of album that features a man punching a pig’s leg as percussion. These albums see Walker at his darkest and most elusive; lyrics sometimes confuse rather than enlighten: “Face on the pale monkey nails,” and “21 21 21.”

Six years later Walker released Bish Bosch with a 22 minute track called “SDSS1416+13B (Zercon, A Flagpole Sitter)” and an eight minute track “The Day The “Conducator” Died (An Xmas Song)” that really push the boundaries of even his last two albums. And then a shocking two years later—late last year— he released a collaboration with Sunn O))), perhaps signaling a creative streak unseen since the Scott albums forty-five years ago.

WHO HE INFLUENCED:

Walker’s reach is concentrated in the experimental set, and David Bowie is a huge fan whose latest offerings are increasingly Walker-esque. He even executive produced a less than spectacular documentary called “30 Century Man” in which a slew of artists talk about his unique genius. (Although, the documentary is a must see for a look inside the studio during the making of The Drift.)

His song “30th Century Man” serves as the template for the cartoon Futurama, and a cover of it ended up on the soundtrack to the movie, and was also featured on Wes Anderson’s Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou soundtrack—not coincidentally alongside covers of many Bowie tracks.

WHY WE SHOULD BE LISTENING TO SCOTT WALKER:

Not many artists dare to do what Scott Walker did, and fewer have managed it successfully. He constantly straddles the line between Pop and Un-Pop, his earliest songs a mélange of rock and standards while desperately inching toward the unknown, the latter trapped in the ether and looking back to those pop tracks he had sung so long ago.

FIVE ESSENTIAL SCOTT WALKER TRACKS:

The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore

Mathilde

30th Century Man

The Seventh Seal

Cossacks Are

Article by: Christopher Gilson