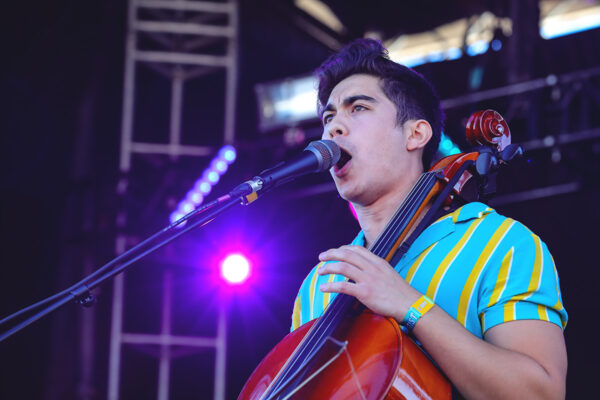

“I’m a big fan of keeping people guessing,” says Jeremy Loops as he winds down from his set backstage at the Mercury Lounge.

Hailing from South Africa, Jeremy has taken his love of performance and melded it with a wicked concoction of looped live tracks, Jamie Faull’s wailing saxophone, passionate vocals and tempestuous rap by fellow Cape Towner Motheo Moleko. The result is more than just feel-good music. It’s arena level jams that have a resonating message intertwined within the melodies. Pancakes & Whiskey sat with the artist after his show and discovered that Jeremy Loops is as complex as his multi-track music.

P&W: When did you first realise music was your calling?

JL: It only actually dawned on me in the last two years. I didn’t do much music throughout my life. I was just one of those kids who used to sing along to everything in the car but as for any traditional training, I have none. I have an honors degree in property development and finance from the University of Cape Town and during those four years of doing statistics and financial maths and economics, I just had all this excess creative energy because I’m a creative kid by nature. I had bought a guitar on my gap years when I was traveling and I spent those four years studying playing music just as a release. I wasn’t pressurized to do anything with it. I could just hear the music and figure it out even without theory or being able to read music. I just feel like I’m a Bob Dylan-esque kid who can’t sing that well, likes hanging out with his guitar and I find it easy to write songs. I just write songs, if you like them, you like them. If you don’t, you don’t. So far it has all gone really well.

P&W: (rapping knuckles on the table for luck) I’ll knock on wood for you on that one.

JL: Oh, I don’t believe in that. I don’t have any superstitions, but I have habits. I do handstands before I go on stage to get the blood rushing to my head so I’m present. I don’t believe that shit just happens, you know? If there’s a problem, it’s probably got something to do with me and I’ll figure it out. It’s all a product of what I either do or don’t do. It makes me feel like I have a responsibility to make things happen and I like that because it’s my life and my career and as long as I feel responsible for it, I don’t ever feel sorry for myself when things go wrong.

P&W: Do you think your structured educational background has allowed you to open yourself up so you can really feel and listen to music in a different way?

JL: I don’t have any hangups about the music I listen to. I have a very eclectic mix of stuff I listen to, like stuff people probably think is outdated. I listen to this one artist, Old Man Leudecke. He’s from Nova Scotia and he’s a banjo-playing folk artist. I’ve been listening to him for 5 years now. He just sings about being happy and he’s a real lover and has great energy. My friends just think it’s like weird jangly music but I totally get him and I connect with this guy. He keeps me in a good space. All artists use music differently. I know people who write sad, downtrodden, like slit-your-wrists kind of music, but in real life they’re super chipper guys. I think there’s a misconception about me because I write happy, upbeat music. I use it to work through the struggles in my life. I come back to it because it makes me happy and I like to be happy which is exceptionally difficult in this corrupt and volatile world we live in run by evil people. But I don’t spend my time writing music about that. I write about things that inspire me and keep me aiming towards the light. I spend my time as an activist working on the social ills that annoy me in a proactive way.

P&W: Do you want to talk about Greenpop, your reforestation movement?

JL: We are a tree-planting organization that started 5 years ago. We plant trees all around Southern Africa, mostly in underprivileged schools and reforestation projects. We aim to educate and uplift communities and try to help eradicate social ills through using tree planting as a platform for social bridging. We find that when people get their hands dirty and plant trees for the well being of the environment, and do so with a bunch of young kids from a underprivileged school, doors open. People find empathy. Thats what we’re all about at Greenpop. You should check us out. You can donate a tree online and we’ll send you the GPS co-ord of where it was planted so you can check it online.

P&W: So is it important to you to be famous, to have a voice in the world so people can look up to you?

JL: I think people looking up to me is the wrong way to put it, but I am obsessed with having a voice. I’m still really small in this industry but I work exceptionally hard at making sure my social media is captivating because I don’t take it for granted that we live in a day and age where the mass media outlets that have fucked the world so hard in the last twenty years are becoming dis-empowered. It’s important to me to have a voice and use it to promote my idealistic visions or just to make shit happen. I was very disillusioned growing up in South Africa where you have a very stark version of what’s happening in the world. We grew up in privileged affluent surroundings as white South Africans, probably more affluent than most people in the US can imagine, and as I grew older the reality of seeing that stark world made me want to do something about it. It was one of the main drivers that brought me back to South Africa and say ‘fuck finance’ and try to find another way to do my part to help make changes. I could see what the 1st World’s role in all of that should be and their complete denial of responsibility.

P&W: But why do you think people just don’t do that, just band together and do that? It just isn’t right.

JL: It isn’t right but it’s difficult. This is where it comes back to “is a voice important to me?” A voice is important because you can’t expect people to sift through things to get the truth. These stories need to be told directly, and not as footnotes.

P&W: Let’s talk about the concept of ubuntu, which was a major theme in the teachings of Nelson Mandela and I know you incorporate it into your way of life. Where can your audience find this message within your music?

JL: The statement is clear — we are what we are because of who we all are. That ties back into what we were speaking about with the 1st World and the 3rd World because you get this one view of your surroundings like in South Africa and you think this is normal. And then you step out of that world to someplace like America or Europe and you realize, hold on, this is not normal. I got an SMS alert on my phone today and apparently it’s called an “Amber Alert” and I asked people what it was and they told me a child had been kidnapped. I was shocked. I asked them if everyone in New York got the same alert and I was really surprised when I found out they had. That’s really amazing. But I mean, who’s sending out alerts that thousands of kids in Africa starved to death yesterday? I am very aware that my stance on these things is not popular. Part of my wanting to build a big network and fast is about ‘how do I get my voice to the size where I’m allowed to say things without getting shut down?’ because before you get to a size where you’re unstoppable, you’re stoppable. So I need to just get past that point. I’m always going to speak to my community like they are my community. They’re not just fans, they are the people who allow me to do what I need to do. No matter how big I get, I will always have a deep respect for those who allow me to play music for them. I mean, I’m just here to play and you’re just hear to listen but in between, let’s talk and act like humans. That’s my ubuntu.

As a final flourish to end the interview, Jeremy was kind enough to pour a shot of Bulleit 95 Small Batch Rye Whiskey down my hatch after he sampled the brown liquor himself. A fitting punctuation for an artist who has found a clever way to navigate through the world in a ship sailing on a musical tide, crossing the oceans with its cargo of truth.

Be sure to check out Jeremy Loops next NYC shows in March and SXSW in April.

Article by: Hannah Soule

Photos: Shayne Hanley