The first thing to learn is that all bourbon is whiskey, but not all whiskey is bourbon. Whiskey could be malt, rye, corn, wheat, bourbon (heck, it could even be rice or oat whiskey, but good luck finding those). There are all sorts of ways to distill grain into alcohol, and these ways are generally maintained by geography and tradition. In Scotland and Ireland, germinated (or malted) barley is the grain of choice. In Canada, it’s rye. In the US, it’s usually a mixture of mostly corn with a little rye, and barley (sometimes wheat) added in for depth/spice. The world is too big and the article is too short to get into all of these designations, but if you’re talking about American Whiskey, you’re mostly talking about bourbon and Tennessee whiskey*. Bourbon is Jim Beam, Evan Williams, Wild Turkey, Four Roses, Makers Mark. Tennessee Whiskey is Jack Daniels and George Dickel. Bourbon and Tennessee Whiskey meet the same legal designations that they are

1. Made in the United States

2. Made of a mash bill of at least 51% corn

3. Aged in new charred oak barrels

4. Distilled to under 160 proof (80% alcohol), enter into the barrel at no more than 125 proof, and bottled at at least 80 proof

Oak Barrels

Tennessee whiskey goes a bit farther adding a step in production called the Lincoln County Process whereby the whiskey is filtered or steeped in charcoal chips before going into the barrels to age. Because this charcoal process is a subtractive, rather than an additive process, and all of the other production methods are technically the same, the taste difference between a bourbon and a charcoal filtered Tennessee whiskey are minimal at best (though I do love debating this point with fellow drinkers and brand ambassadors). When your friend points out that Jack Daniels is not bourbon, you can know that Jack meets all the legal requirements of bourbon and tastes like bourbon, but it just chooses not to be marketed as bourbon.

The real question is not the legal distinction between Tennessee whiskey and bourbon, but what kind of production methods make the sort of whiskey you want to drink. The step of charcoal mellowing is one small part of the process. There are so many other questions that affect what’s in your glass. How big is the distillery? Where do they get their barrels? What size are the barrels? What char level? How long have they been making whiskey? How long has that whiskey been sitting in the warehouse? How many stories is the rick house? How do they move their barrels? How do they decide one is ready to be bottled? What proof is it? How many cases do they ship in a year? I went to Cascade Hollow in Tullahoma, Tennessee with the question of what distinguishes Tennessee whiskey from bourbon. It turns out there’s more to look for in an American whiskey than just the label. In Part 2, I’ll dive into the rise of craft whiskey and it’s new place at the table.

*Jack Daniels spells it “whisk(e)y” while George Dickel spells it “whisky” (the original Scottish spelling) because, as the Dickel brand ambassador told me this week “George thought it was every bit as good as the finest scotch.”

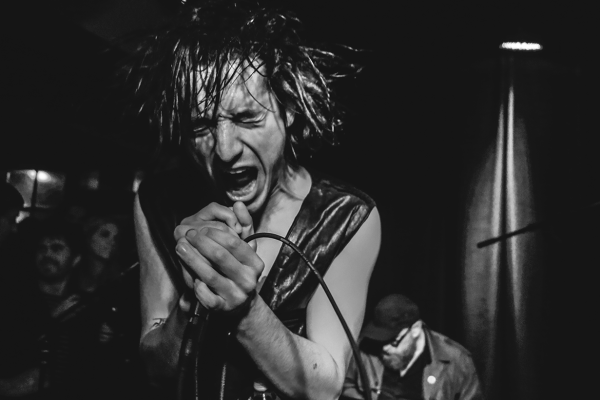

Article: Tyler Lyle