“I feel like I forget the processes of the past, for good and for bad.”

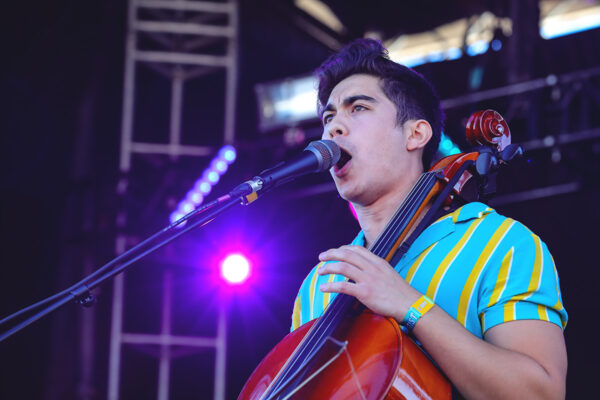

The sands of time can be unforgiving. Although for all the years he’s spent making music, the clarity and sentiment that flows throughout the Langhorne Slim songbook has yet to be lost to the wild. Projecting the poet’s candidness that’s always been woven so neatly into his voice as a songwriter, the Nashville based musician –born Sean Scolnick in Langhorne, PA- peppers his sixth album, Lost At Last Vol. 1, with stories that take shape in the light and the dark, fraught with nostalgia, elation and the type of redemption that doesn’t come easy. Painting pictures with chords and notes, his newest songs combine bare bones folk with whispers of rhythms swift enough to rival the rolling channels of the Mississippi. “I had -in some little vintage store- found a pin like a year or so ago that said, ‘lost at last’ on it and I bought it and I loved it,” he remembers of the chance find that would later fit so perfectly as the albums title, before explaining how for him, the phrase echoes a desire to not be confined or weighed down by anything, but to always grow and search and be inspired. “That’s what I mean by it- not lost in a reckless way or a way of not knowing where we are. But maybe to shake my own self up to get closer to where I want to be or starting to just attempt to poke holes in my own individual bubble- even one little hole if you can poke through it and some new light shines through. Then there’s new opportunities, there’s new ways to see things, there’s new ways to feel things and therefore if you’re a songwriter, there’s new ways to write.”

Producing an atmosphere framed by a palpable sense of instinct and ease, Lost At Last orbits around contrasting scenes and sounds that glow with the shadowy beauty of the place that he credits for inspiring so much of it: New Orleans. It’s a connection that’s felt most on “House of My Soul (you light the rooms),” “Money Road Shuffle,” “Alligator Girl” and “Bluebird,” but –much like the city itself- the unchained spirit of it all has a way of staying with you. Although on one of the records brightest moments, he celebrates another corner of the world that has stayed with him since childhood. As brilliantly tinted as an old slide, “Ocean City (for may, jack & brother jon)” will leave you barefoot and young in the salt air and unsteady on the shore, holding sparklers that flick color into the night at a time of day when the only other gleam is from ferris wheels that tick and rotate like the hands of a clock. “Sometimes you get to be a vessel for something that moves through you,” he says of the many magical, mysterious ways that a song rises to life from a patchwork of memory, experience and some other unknowable component that can’t be easily explained.

“It comes from some other place and we are just vessels, whether you are a painter, a writer, you know, when you get into a zone, runners chalk it up into some like runner high or something. It’s the same I think for creative people. Therefore, when I start thinking -and I’m an anxious young man at times- like I can really get in my own way with my thoughts. But I really just wanted to tear the house down in that way and whatever I was fortunate enough to flow through me, to not stop the process by over thinking it by wondering if I liked it, if my label would like it or whatever or if people would like it, and just do it as purely as I could. Trusting that if I did that, if at the end of the day nobody liked it, it didn’t matter because I know that it’s real. I know that it’s real for me. And that’s what I need as a guy that’s been doing this since I’m 18, 19 years old.”

Beginning initial sessions with a band of friends in Stinson Beach, California, he embraced an in the moment approach that aimed to peel back the layers and simplify the process. “I didn’t want to think about any of it,” he says. “I just wanted to feel.” Essential to following that path was taking on a rapid pace, something that produced its own set of challenges when the two-week timeline he originally had in mind hadn’t felt like a natural end. “It took quite a bit longer, which was difficult for me because I really just wanted it to be done and I really wanted to make a record that just wasn’t over thought and that was like I’m saying: you push record, you record the tunes, you get the feeling and the wildness and the vibe of people playing in a room and then move on to whatever my next project was,” he explains. “But because I still felt that the work wasn’t done and I wasn’t going to put it out until I was completely ready to, it caused me to have to break through some walls of looking for the light and the beauty that was in it not being done yet.” Although in a serendipitous turn of events, it would eventually be completed in NOLA after the musician rounded up a group of Louisiana based friends and artists including Aurora Nealand, The Lostines, The Lost Bayou Ramblers and keys player Casey McAllister of the Langhorne Slim led band The Law. “[I] got us this little backyard studio and I remember I was in California and I really like to go to steam rooms, it’s become like a meditative thing for me since I quit drinking and stuff,” the now sober musician recalls. “And I was sitting there and I literally started to cry because I realized I’d been so frustrated and then I realized how fortunate I was to take this record, this music that was so inspired by this place and bring it there and have these friends -that really are, again, people that I’m fans of that have become friends- to contribute to the record and to help me finish it.”

Emotionally bare and wrapped in harmony that begs to wipe the slate clean, album closers “Lost This Time” and “Better Man” both touch on painful allusions to the past and visions for a greater future. But like much of the encouraging, resilient nature that’s often found in his work, it’s a hope that remains fragile, grounded in realism and -as so often is the case in life- it’s an optimism that you have to fight for. “I’m not further along than anybody else and I’m continuing to sing for myself as my own therapy and it’s my own reminder because I deal with -we all deal with- sadness, with bouts of depression, anxiety, addiction, whatever the thing is, we all have our creatures that lurk within,” he says of his own motivations to write before later discussing how hardship’s universal grip can be an inherently unifying thing. “That should be what brings us together; that we’re all struggling within. We’re all scared weirdos running around. And a lot of my music, I think whether I’ve consciously tried to touch on those themes or not -I mean a lot of times I have it wasn’t conscious- but it’s something I identify with because I am a human that is full of love, full of optimism and full of hope, and at the same time, deal with my own creatures and my own deep dark places.”

It’s perhaps because of that willingness to go to those deep, dark places in his music that he enjoys such a rare kinship with his audience, who are sure to find there own inspiration in the always keep moving ethos Lost At Last evokes.

“I have a friend who buys his art from this old man who makes this beautiful folk art,” he says before sharing the words that mirror his own desire to always work from a place of sincerity. “He was talking to this old man one time about how he makes his stuff and I guess the old man told him, ‘Sometimes I study at the divine university.’ I don’t know exactly what that means to him, but I know what that means to me and that is just to -it’s not religious per say- it’s more getting out of our own heads and more into our own hearts and living from that place.”

Article: Caitlin Phillips