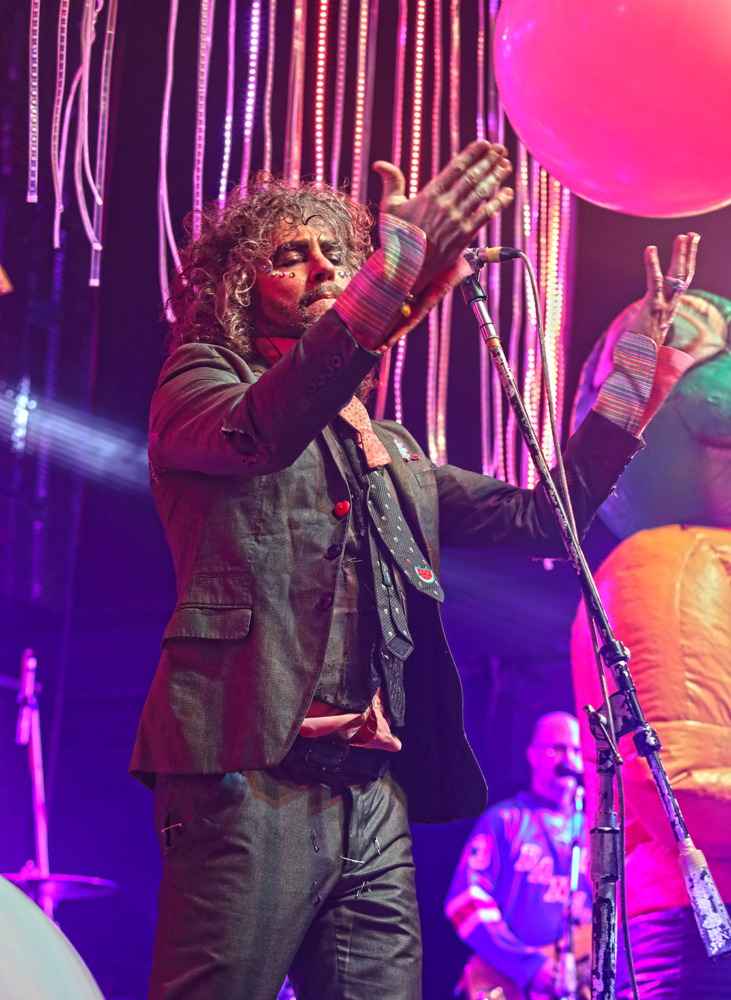

Wayne Coyne must have been in the mood to talk, because an ordinary day took a wild turn when I found out I would get to speak to the revered frontman in just a couple of hours. I was too excited to sit still and nearly sprinted in circles until the phone rang. Having dug the Flaming Lips since an age when I rode the school bus, I impulsively jotted down dozens of possible questions. Whenever I tried to reduce the list, I thought of three more things I wanted to ask him. Ironically, when the time came, Coyne started interviewing me instead. “I love this name, Pancakes & Whiskey. What is that all about?” he demanded with the tone of someone hiding a smile. And that’s how, to my surprise, a call with one of the eminent innovators of our era kicked off on the topic of breakfast. Just as suddenly and unfathomably, it tumbled into much deeper subject matter.

“I like them pretty normal,” Coyne said of his pancakes. “Lots of butter; lots of normal maple syrup. I like some blueberries, but I don’t like it getting too frou-frou. I don’t like too many weird things in there, you know? Sometimes it just becomes a giant dessert with a pancake in the middle of it – whipped cream and strawberries. We could just have like, cheesecake, or ice cream,” he laughed. “And I always like something that’s like bacon. Either real bacon or fake bacon or something, just to kind of give you that little bit of contrast. But plenty of the butter. Because without the butter, again, you don’t get that other rich savoriness. With whiskey, I don’t really even know. What is Fireball? Is that whiskey? I get like an acid reflux thing; I’ve noticed if I’m at a bar and I get a shot or two of Fireball, it will get rid of the acid reflux – like if we’ve gone out and we’ve eaten some tacos or done some cocaine or something. And I’ve discovered that it gives me this relief. Sometimes I will just drink some because it gives me the relief from that. And other than that, I don’t really think I would drink whiskey. I wouldn’t have too much of a preference. I think there’s even a Flaming Lips whiskey out there – it’s a rye. Is that a type of whiskey?” He was referencing a limited-run collaboration with Few Spirits named Brainville Rye that is already a collectible. “But I’m pretty easy,” Coyne noted. “Whatever everybody is having – I would have that. I wouldn’t be too contrary.”

There’s no smooth transition from tacos and cocaine to a record about a giant baby, but somehow, we changed gears; his freshly pensive perspective on everything made the conversation effortless. Given that the new Flaming Lips album, King’s Mouth (released last month) supplements a bigger story and full-body art experience, Coyne explained how they’d ended up going down that path. “In the initial installation, we did make two slightly long pieces of music. I think one of them was like fourteen minutes, and one of them was thirteen minutes or something like that, and those would play inside of it. It’s easy to look at King’s Mouth and see what it is, but the real thing is when you go inside of it, which is like this insane, synchronized, liquid LED fuckin’ hallucination. You can’t really describe what it is. That’s why we have the king’s mouth, and the tongue, and the teeth, and all this stuff, because at least you can see that as the thing that you crawl inside of. So we did have two big pieces of music that initially played in that, and then we chopped those down to where it was just about ten minutes long that you were in there. It was two tracks on the album: “Mother Universe” and “Electric Fire.” Those are the instrumentals that would play if you’re inside the king’s mouth doing the installation. And as we got those more honed down and more precise for the album, we did the same thing in the installation. So you go in, and when you’re laying inside the king’s mouth, looking up toward the endless universe up there, it’s only about six and a half minutes long. But because it’s kind of abstract, it’s hard to know where the beginning is and where the end is. If it’s not a real busy day at the installation, you can sit in there three or four times and not really know that you’re seeing the same thing over and over, because it’s just so fun.”

“So this installation, when it first came about – people would see it, and they would ask us, ‘Well, is there an album that goes with this?’ And for the first year or two, we would just say, ‘No no no, not really; it’s just this stuff.’ But then the curator at the very first art museum that it got to go to – he encouraged us to make some drawings and make a little story out of it if we could. So the more it went along, we thought, ‘Why don’t we just make some songs that go along with this sort of silly story?’ We already had a little bit of the story. In the beginning, we thought it might even just be instrumental. So I think everything about it sort of being not that serious and not that important, as to what it is, I think all of that helped it be really, really great and simple. I think if we thought, ‘Well, we have to do this epic story about this epic giant baby that grows up and gets his head cut off and saves the village from this avalanche,’ I mean, we would have overdone it. But because we didn’t really think that it should be a normal record – we were just thinking, ‘Oh, it can be anything, because it’s just going to accompany this installation’ – I think that helped it just be simple. To me now, I hear the songs and I’m like, ‘Hey, these are just some really great simple songs.’ And I know if we thought it had to be songs in the beginning, we probably would have messed it up. So I think that’s a good lesson for us to learn: just don’t try so hard to make it something. Let it kind of become something.”

King’s Mouth – essentially an expanded soundtrack to a sculpture that even comes with a hardcover book – reflects Coyne’s stature as a Renaissance man. His artwork, music, and writing, as well as his propensity to ponder life, death, science, and space, seep together in an experience that stretches far beyond a record. I wondered how he’d respond to this perception of his creativity. “Well I think if I introduced myself as a Renaissance man, it would sound horrible,” Coyne said with a laugh. “But when people say that, I’m like ‘Yes! I agree!’ But I would think everybody would be interested in all of that. To be interested in one just opens the door to another. How can you not just see everything in the world and think, ‘Man!’ you know? Music, of all the things, is just such a mysterious, powerful experience. I mean, you can look at a painting as long as you want. You can look, and look, and look at it, and it can be a very powerful thing. But music is like a potion that you take. A song can last three minutes long, and from the beginning of it, it starts doing its work on you. And by the time it’s gone through you, three minutes later, you’ve kind of had this weird experience. And even though you may have had it a thousand times, it still works its potion on you. It’s weird. I think that’s why, for people who make movies, the most powerful scenes in movies are powerful because of the way they’re using music, and sound effects, and story, and momentum, and all of these things together. But take the music out of movies, and it’s just not the same saturation of that heightened emotion. Emotions, in real life, just don’t happen that fast. Nothing happens piercing you right into the internal core of whoever you are. That’s kind of invisible to you; you don’t really know who you are. But music that you really fall in love with, it’s penetrated that, and you get to go to the core of who you are,” he said, very tenderly. “Then it’s over and you come back. And it’s funny, because you can really be having just a normal, nothing kind of day, and you can hear some music, and within a couple of minutes, you’re kind of crying. And someone says, ‘What’s wrong?’ and you’re like, ‘Nothing’s wrong. I just heard some music.’ And then you’re back to normal after it’s over.”

“When I was growing up, because I was always encouraged to do painting and drawing and all of that, when I thought, ‘Well, I want to do music too,’ everyone around me was just so encouraging. They were like ‘Yeah! Well, Wayne, you should do music too. Just go for it!’ I think that before I was able to discover that I’m not very good at music, I was already making records. It was only when I ran into someone like Steven [Drozd], who’s such a master – not just insanely talented, but a really hard-working, smart musician, I realized, ‘Oh, I don’t know anything.’ And by the time we got together, he liked that I had confidence and momentum, and that I would create things. And I liked that he would create things, and I could fill in the gaps where it needed momentum and stuff. So I think the things that we sort of felt like we were lacking, we found in each other. There are always references to how The Beatles bickered amongst each other and all that, with a lot of bands. But really, with Steven and I, I mean, I am like his biggest fan. I love his music, and I think he is the same with my music. So whenever he’s making a song or something, I’m the first one who gets to hear it. It’s like ‘Oh my gosh!’ He wants me to help him cobble it together to make it a complete thing. And then I’m doing the same thing with my simple songs. They need some help, they need some musical-ness, they need some momentum; some connection. And all those things that I’m not good at, he’s like the master of. So I think it’s just a bizarre combination of personalities that allow The Flaming Lips’ music to be what it is.”

One prevalent trait in The Flaming Lips’ lyrics is their ability to help listeners approach more daunting, serious topics about the universe through an innocent, often childlike lens. I asked if this was intentional, pointing to the pleasing simplicity of lines like, “It made me understand that sometimes life is sad,” from King’s Mouth. “Well,” Coyne reflected, “when I hear what I think of as our best lyrics – and I think that’s a really great one that you’ve pointed out there – to me, it’s only because it sits in this music. To me, the music is already telling you all of that; even the tone of my voice and the notes of my voice. I almost feel like I could say nothing. I could just be saying ‘blah, blah, blah.’ I could just be saying gibberish, and it would almost have the exact same effect. So sometimes, I sort of feel like, if I say this very simply – but almost bordering on ‘That’s so simple…are you sure that’s gonna work?’ – that’s where this collaboration with Steven comes in. I’m gonna sing this, and it’s either gonna work, or it’s not. And he’s gonna be able to hear it and say, ‘Man, that’s a motherfucker.’ He’s gonna know that it works. So I think we’re lucky that we have the ability to trust that, ‘If it works on you, then I know it’s gonna work.’ Because I would agree with you – it’s so simple. Maybe that’s why I like pancakes that way. Just some butter; some syrup. I don’t want to frou-frou it up too much.”

“My lyrics without the music – I don’t really even feel like they’re poetry. I think, if you know the songs, you can recite them, and you can remember them and know what they are as words. But I would never just hand someone my lyrics and say, ‘What do you think of this?’” Coyne said in a funny salesman tone. “Because the music is doing so much. The music is so optimistic, and so understanding, and so encouraging. I mean, sometimes people talk about our song, “Feeling Yourself Disintegrate,” and I don’t really like talking about the lyrics without the music. Because the music is giving you so much. The music loves you so much that you’re able to confront these sometimes brutal, really painful things, because the music is like this great, warm, loving, mother blanket around you saying ‘It’s alright,’ you know? And to me, to say those words without that loving blanket of beautiful music, it’s like – I don’t want to say those. I only sing those within the song. I don’t really say them in life, because I feel like they are kind of too brutal. It’s almost too brutal to believe. But music just does that. Music can open up parts of your mind that you don’t quite understand. To the worst unimaginable things, music says, ‘I understand. We’ll get through it,’ and it’s just magic. So my lyrics; that style – I agree that we do that, but I only feel like we do it because that’s what the music would want me to say. I’m just a human. I’m just trying to say these things so that we can understand them, as opposed to making it complicated, or making it abstract, when it could be such a simple, direct thing.”

Being that he’s such a fearless creative force, I wondered if Coyne had advice for fellow creative humans on finding their place in this world. He did, of course, and even went so far as to break it down for two personality types. “A lot of artists are introverts,” he told me. “That’s kind of the nature of just sitting there by yourself, creating a world. You’re not the life of the party. You don’t often even want to be at the party; you’d rather just be home painting, so you’re just this weirdo introvert. But a lot of music is done by extroverts, and they’re just the opposite. They don’t want to sit in the corner by themselves. They want to be the life of the party; they want to be the only one talking; they don’t want to listen; they just want to blab, blab, blab. But it works both ways. People who are extroverts, they want to be introverts. They want to sit in the corner and make something; they want to be able to do that. And people who are introverts want to be able to stand up in front of people and say outrageous shit. Everyone is struggling for the other side. So what I try to tell introverts is, you’ve just got to go out there. No one is going to hear you if you don’t say stuff. People will only listen to the person that’s talking the loudest, and sometimes it’s rude, and sometimes it’s not appropriate, but if you want people to hear what you have to say, you still have to do it, even if it’s not something that comes naturally to you. And if you’re an extrovert, and you want people to take you seriously and not just be an entertainer or whatever, well, then you have to go internal. It’s hard! It’s not natural.”

“So for Steven and I – especially in this way that we flip flop; being the weirdos sitting in the corner making our intricate personal music, then we walk out one door and we’re standing there onstage, having to do this music in front of all of these people – we’re very glad to just be entertainers at that point. We don’t ever stand up there and think, ‘Look, we’re artists, motherfuckers.’ If we’re up there on the stage, we know that we’re just entertainers. And it’s a service. We don’t look at it like we’re important. We look at it like, ‘We’re glad you’re here, and we can perform this service for you. You’re here to see us do these songs.’ And that relieves us from all that other stuff. To a lot of people, the word ‘entertainer’ – especially for people who consider themselves artists – if you say you’re an entertainer, they think, ‘Well, that’s bullshit. That’s nothing. You’re just kissing everybody’s ass.’ But to me, whenever I go to see bands play, I want them to be entertaining. I want it to work. I want them to be happy. I want them to express themselves. I want them to be glad to be there.”

“I mean, I remember the first time we played with Nirvana, even before their first album came out. We had an advance copy of their Sub Pop album [1989’s Bleach]. We knew all those Sub Pop guys before they were Sub Pop. We had Nirvana play a couple shows with us before it even came out. But their very first song that they played, the microphone wasn’t on. They ran through this whole song like it was fuckin’ the greatest thing ever; like they’d never played it before. And then, when it got done, we said, ‘Hey man, the microphone wasn’t on, so, damn.’ And they said, ‘Fuck it,’ and they just did the song again. Like ‘Alright, who cares? We’ll just do it again.’ And you think about a temperamental artist – and I’m sure people even thought Kurt Cobain, perhaps, was like that – an artist would say ‘Hey, fuck it man. I did it, and that’s all there is to it.’ But it’s not like that. You want people to get what you’re saying, and you want people to get what you’re about. You want people to like it, and you want people to be with you on this stuff. So to sit there and be able to play this music every night, it’s like doing any kind of art, in a way. You get better and better. You get better at understanding the audience; they get better at understanding you. You get better at getting through the things that are bad or awkward.”

“My advice that I would give to any artist that thinks that it’s magic: don’t worry about it being magic. Just work at being a really good artist. Work at being a really good person. And if you do that, you might get lucky and then do something great by accident. But if you try to just be a genius; you try to just do great work and you try to be whatever, it just doesn’t work. You just have to do it, and do it, and do it, and do it. And if you get lucky, maybe something great happens. And if you really work hard and long, and long, and long, then maybe you get lucky and two or three great things happen. But it’s not because you’re great, or because you’re a genius, or any of that. None of that is anything. Just do the thing that you love to do. Just work at it and work at it. You know, other artists and other musicians always come to your rescue. I mean, that’s absolutely true. You could be playing to a hundred people that aren’t artists or musicians and they may like you or be indifferent. But if you’re doing something cool, another musician or another artist in that room, they’ll hear it. They’ll know. And they’ll let you know. Musicians and artists always come to each other’s help. That’s just the secret code.”

Since Coyne has always been vocal about things like taking care of the environment and making a positive change in the world, I was curious which causes he’s focused on right now. “I feel like everybody’s most powerful thing that they can do is in their own family and in their own neighborhood. In my neighborhood, where I live, I’ve lived in the same neighborhood since I was a teenager, and I’ve lived in the same house now for almost thirty years. And where I have the most impact is helping my neighborhood, and helping my little district there. I know what’s going on there; I know everybody there.” Coyne then stressed the importance of “Voting and caring about your local issues,” adding without any prompting: “I don’t even like to talk about Donald Trump. To me, he’s just so meaningless. But I’ve never waited or expected or wanted any president – even when it was Barack Obama, who I love – I’ve never waited for a president to tell me how to live. That’s just not what they’re doing. And if you come here, there are so many homeless animals, for some reason, in Oklahoma. I’ve been all over the world, and I’ve never seen a place that has more homeless dogs and cats. So every day, we’re always making an effort – you have to be kind to animals; you have to help them. Our shelters have been overloaded there for like twenty years now. So we’re always making an effort to be like, ‘You don’t have to go adopt an exotic dog; you can just go get one that’s on the street right now and give him a good home.’ And we always talked about how ridiculous the marijuana laws in Oklahoma were. Little by little, all of that’s changing. But it does take a true commitment. You have to care. You can’t just care when it’s convenient. You have to care all the time.”

“I think little by little, everybody does care about those things, and they do like that it can be slightly organized so that the thing that they care about – they can do something about it. So I always remind people, don’t worry about who the fuckin’ president of the United States is. Worry about who is helping you right there in your neighborhood, in your little part of the world where your one vote really does make a difference. A lot of times, we’re voting in our little part of the world there, and two or three votes is all it takes to win! People always say, ‘Well, my vote doesn’t matter,’ and I’m like, ‘It does. In the right place, it really does.’ And as we start to talk about if Trump is going to win reelection or whatever, I’m like, ‘Of course we should vote for a president; we should vote for everything else.’ But for me, this is the strangest thing ever – the day we woke up and we were discovering that Trump was now going to be the president, Oklahoma City, at the same time, had passed some new laws about marijuana and liquor, and lessening some of these prison sentences. These were things that we had fought long and hard for, and they became true. So on the day the worst thing in the world happened to the country – Donald Trump gets elected – the best thing in the world happened in Oklahoma City, right where I live; right where things have an impact. So to me, it’s like, vote on the shit that’s gonna affect you, and your friends, and your family, and stop worrying about Donald Trump. Because if you spend all your time worrying about him, you forget about the things that you could really change. That’s my advice.”

It’s never easy choosing the last question, especially with someone as thought-provoking as Coyne, who seemed so open to discussing any subject at length. Before I let him get back to exploring the secrets of the universe – or more likely, spending time with his new baby boy, Bloom – I asked which of their many albums he considered his favorite. “Well, these records of ours that are celebrated, like The Soft Bulletin [1999] and Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots [2002] – we’re part of them being celebrated,” he explained. “We’re always so blown away that these records have an impact beyond just weirdos who like weirdo music. Steven and I talk about it all the time: we really are making music that’s just kind of invisible; you can only know what music you like once you start making it. We just follow whatever that urge is, wherever it takes us. We know that we would never have an urge to make a record like The Soft Bulletin again. It just comes from an internal urge to make something that doesn’t exist. Once it exists, if you’re the one who made it, you really wouldn’t have an internal desire to make another one. But I know when we made The Soft Bulletin, and the next year after that, when we made Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots, it was a time when we did have these records in us. And if we hadn’t made them, we probably would not have wanted to make records.”

“There was something in us that was like, ‘We want to make these types of records,’ and if we couldn’t figure out how to do it, whatever it was, we would just blame ourselves. But we probably would not have wanted to keep making records. So I think once we were able to do something like The Soft Bulletin and we saw how much of an impact it had on us, and how much of an impact it had on people who would come to our shows, who would talk about it – that’s a great, great thing for an artist. To be so insecure, but always have these things there that are saying, ‘You can do it,’” he laughed. “‘Keep trying! You can do it. Don’t worry about it so much.’ Those two records are so optimistic, and they’re so encouraging, even for us when we hear them, even though we made them, they encourage us too. There’s no way that those wouldn’t be our greatest that we’re proudest of. We’re proud of all the things that we do, but when those things go out there, they really come back to help you too. They’ve come back to help us, probably even more.”

Article: Olivia Isenhart

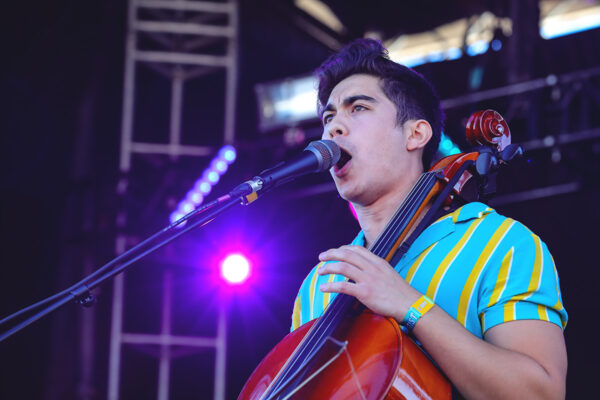

Photos: Shayne Hanley