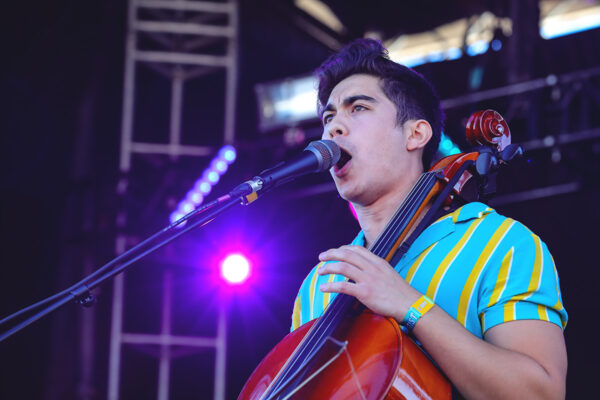

In a room upstairs at Rough Trade that I had never noticed before – where I got to talk to Twin Peaks’ Clay Frankel and Cadien Lake James – there lives a nice collection of vinyl that I was much too excited to peruse. I didn’t want to burst into questions before we’d officially started the interview, so I stood back and quietly watched Frankel pull out The Velvet Underground & Nico and kick back on the table; I glimpsed Warhol’s pop art banana from across the room when he flipped it over to read the back cover. Simultaneously, he sighed and shook his head with real admiration. I felt right at home observing his natural affection for sixties rock, and it reminded me how well-studied and classic their own songwriting often sounds. This is especially true on Twin Peaks’ fourth studio album, Lookout Low (out today), but I wouldn’t receive a sneak peek of that gem until a few weeks later. At the time, all I had was the memory of their energetic, free, crowd-pleasing festival performance at Vermont’s Waking Windows a few months prior – and the screams that surrounded them incessantly. So that’s what we talked about first.

“A lot of the times, it doesn’t feel like we have any star power,” James (a.k.a. Big Tuna) said amusedly. “So when stuff like that’s happening, it’s a hoot and you laugh about it, I guess – right?” “Yeah,” Frankel agreed. “It’s funny that people yell at us when we set up. Every time a group of people is cheering, it surprises me. We opened up for PUP, and we’re our own roadies and all that. So you play, you walk off, and stand there for about ten seconds, and then you’ve got to go back on to get your stuff off. You know, you come back out and people are like, ‘Oh my god! AAAH!’ and it’s like, ‘No…I’m just gonna wrap my cables up.’” Both guys snickered. “It was funny!” said James. “Whoever was doing lights, when you walked back on, he spotlighted you. And people were like, ‘Yeeaaah!’” Frankel reacted with a surprised laugh, “Oh, did he?! I was wondering, because people were really cheering loudly when I came out to just get my pedals and stuff. I think part of it was because they forgot to put music on; music kind of tells people that the show is over. So maybe they thought it was another song or something…and I guess the guy threw a light on me! It’s weird for people to cheer like that. But it’s wonderful having fans.”

“Some cities, we’ve been told, are notoriously stiff, even for kind of lively music. You know, people tell us, ‘Nobody’s going to go crazy here,’ like in Nashville or maybe Seattle or something, but we’ve never really found that to be true. I think it’s just…” Frankel paused pensively. “We shake it up there, so people are more invited to join in.” James added, “It almost probably sounds funny to say, like it’s a cliché at this point or something, but I’ve been saying it forever and just think it’s true: I really feel, the way we see it is, if we’re not having fun up there, how can we expect anyone else to have fun? So, almost more so if it’s a really dull show, me and Clay will just be fucking with each other. I headbutt him a lot.” Frankel responded with a funny business-as-usual look on his face, “If I fall, he’ll come and sit on my head, or kick my butt or something.” “Especially if the crowd’s not giving me anything,” James commented. “I’ve got to fuck with him.” A quiet crowd was certainly not the case at Waking Windows, during which Frankel appeased one of their many squealing fans with a dollar bill origami ring he had folded mid-song. “I’ve never seen him do it before,” James said of that occurrence. “No. I just must have just been playing with a dollar,” Frankel replied. “Any fan’s special, as long as they’re kind. As long as they’re not assoles in the crowd, they’re special.”

Given their onstage synergy, I wondered how much time the guys spent jamming in their down time and how often it engendered new material. “That’s how it comes together in its final form, for sure,” noted Frankel. “We did a lot more writing together on this last record, but we’ve always been writing little songs in our own time, and then bringing them to the band, and then evolving them.” James nodded. “We give anything a shot. And some songs you wouldn’t expect to end up being the highlight for yourself or something – once you bring it to the band and everyone fleshes it out, it’s like, ‘Oh, this is great.’” On that subject, I asked how many songs came to them quickly in that fashion, and how many were a long-term labor of love. “There have been a couple like that on this record,” he explained. “The song we just put out is a song Cadien wrote a long time ago,” Frankel said of “Dance Through It,” Lookout Low’s first single and music video. “Like what – high school? It evolved.” James replied, “It was probably like four years ago or something. It was not like it is now. It was just like acoustic. It wasn’t swung. Totally different vibe. Same vocal melody, same chords, same lyrics, but other than that…” He trailed off, agreeing that Twin Peaks’ sound on the whole doesn’t fit squarely into any one genre. “I feel like it’s not shocking when we don’t sound like we sound. Definitely.” Frankel added, “That’s why it’s also easy to try whatever idea we have, because there isn’t really a mold to fit it in, so anything could work out.” James then summed up their whole vibe beautifully: “If it feels good, it feels good.”

Knowing that Twin Peaks initially demoed twenty-seven songs for fourth album Lookout Low, rehearsing each one relentlessly before narrowing them down to the ten that made the cut, I had a mystery to solve. “Where do all of the songs go?” Frankel repeated with a cryptic grin. “I’ve got a vault.” In terms of unused material, James agreed, “He’s probably got the most out of any of us.” “Maybe,” Frankel replied. “I think we all do. It’s just like a painter or anything; we’ve got sketchbooks, you know?” The next question, of course, was whether or not we’d ever hear the songs that had ended up on the cutting room floor. “I don’t know…who can say?” Frankel teased. James leaned back and said coolly, “Never say never…” “They still might be songs that we put out later on,” hinted Frankel. “It’s good to have ‘em. We’ve got ‘em.” Discussing the inspiration behind Lookout Low, he recalled, “We were listening to a lot of live records on tour and stuff. I really love Tonight’s the Night in particular, by Neil Young. And we listened to a lot of Grateful Dead as well; like the live concerts. And somewhere along the way, we just decided we’d do the whole record live, so it was kind of just kind of a loose performance.” Then they shared how they’d ended up recording it in Wales with producer Ethan Johns (Paul McCartney, U2). “It was kind of a crazy situation, how it happened,” noted James. “Just heard a record and we were like, ‘Oh, who did this? Oh, Ethan Johns – who’s that? Oh, it’s fucking Glyn Johns’ son – he’ll never do a record with us. Hit him up and he was like, ‘Yeah, sure.’”

“He lives out in England and he wanted us to come to Wales, ‘cause he has a family and doesn’t work on the weekends.” Frankel chimed in: “We didn’t know that yet though…” “No we didn’t,” James laughed. “We didn’t know ‘til we got there.” “So we did…how many in total did we do? We did like thirteen in ten days. A lot of them are first takes. He’s chill,” said Frankel. “He’s such a laid-back dude,” agreed James. “He walked in first day with a Dead shirt on. He’s got this big white beard, long hair, and glasses. He’s just a pretty loose, freewheeling guy; very calm. We talked about Lord of the Rings a lot, and like, Stonehenge and shit.” “Yeah he’s really into like British lore and mysticism,” Frankel recalled in a sweet tone. “He’d tell us about that; we’d have dinner together, because we lived at his studio-house. It’s a studio that you live in when you work there. We really didn’t know what to expect at all. I don’t know if any of us had met him face to face – did you?” Frankel asked. “No,” said James, “no, definitely not.” “So we were really hoping it was gonna work out, and it did. We met him face to face and he was just really relaxed, and pretty much every song we played him – he had probably heard a lot of demos – but every song we played him, he was like, ‘Oh, I love it.’” The guys laughed in unison. “We were like, ‘Oh…do you want to try it a different way?’ and he’d be like, ‘I don’t know; just roll it!”

“A takeaway, for me,” said James, “that I hadn’t had yet: there were songs where we’d play the first take, and we’d come back and listen, and we’d never tracked live – we weren’t used to hearing our voices like that. And I’d be like, ‘Oh no, fuck. This is fucked. We’ve got to do it again.’ And he’d be like, ‘It’s beautiful. I cried,’ or whatever. He was so into it, and he’d tell you, ‘This is the one.’ It took a little bit to get into his perspective and how he was seeing it, and listening to the song rather than your part. You know, it’s all very nitpicky when you’re doing just the drums or just the guitar, and focusing so much on it – whereas when you’re just playing all together and you listen to it, you kind of have to force yourself to stop listening to your instrument, and listen to the song. And it took a little bit to get into sync, but once I did, I was like, ‘Oh, I kind of get why people like our live shows so much.’ We never get to see our show, or we get to listen to it from like a shitty stream afterwards or something, and to do it that way, it was definitely reaffirming about our chemistry in a room together.”

“It was daunting to be in a very nice-looking studio,” Frankel explained. “For him [Johns] to still hold true to keeping the imperfections is good – because you kind of feel the pressure of that really nice studio; like we should be playing perfectly, you know? But it was a still-keep-the-mistakes attitude.” Even so, I wondered if that polished environment made it more challenging to cut loose like they do in the live setting. “Clay set up a little candle spiritual room,” said James. “There are little things I would do,” Frankel shared with a shy smile. “I tried to collect items from all over the house that had good energy, and candles and stuff. I asked the studio hand, ‘Can I light candles in here?’ and he was like, ‘Hmm, I don’t know…’ and I was like, ‘I’m…gonna light some candles,’” he laughed, “because you have to do something to make it not as sterile. So there was a little closet that was sometimes used to sing vocals in while he played, and I set up a little thing in there. Yeah. A little altar. Wherever he put me, I would try to set up stuff around me; little plants and books and good stuff.” “Also,” James chimed in, “when it was feeling good, playing with everyone, I would catch myself with headphones slipping off, just jamming out a little bit. Because, you know, fuck it. You’re playing rock and roll with your friends.” “It was actually funny,” said Frankel, “because a lot of times, it would take a few hours to set everything up; all of the microphones. And then you’d play a song once or twice, and you’re having fun, so you wanted to just keep doing it, and he’d be like, ‘We’re done.’” Frankel laughed incredulously. “‘We’re onto the next one.’”

“The Chicago band OHMME, who are friends of ours, sing a lot on this record,” he noted. “Great band in the Chicago scene,” commented James. “They’re all over a lot of people’s stuff, ‘cause they’re awesome and great to collaborate with. We wanted them to sing on the record, and they were talking to us about how they were doing this U.K. tour, and we were like, ‘Oh that’s great. We’re going to Wales. Is there any way we can line it up and have you come to the studio? And they came out for one night and an afternoon, and they knocked out ten songs in one day. You need a feminine presence sometimes.” “Yeah, to kind of smooth it out,” agreed Frankel. “I mean their voices are just…beautiful. And that makes it fun too, because it’s more fun for me to listen to someone else’s singing.” He went on to break down their process with a grin: “You just write the songs, and when you have a bunch of ‘em, you just carve out an album’s worth, and that’s where you’re at right there. They really gel together pretty well on this record, I would say. The live element might be a lot of that too, because…I don’t know,” he said with a quick laugh. “You’ll see.”

Getting to glimpse Twin Peaks’ collaborative process and studio time so vividly was a treat. Getting to hear James’ thoughts on current events was a comfort. “First thing – let’s get the kids out of the fucking cages. That’s a big one in the country right now that’s just fucking insane. I guess, generally, there’s so much going on nowadays. There’s too much to focus on one thing, almost, you know? And we have access to all the information, and it can be really overwhelming for everyone. I know most of us in this country who care feel that. It’s easy to get apathetic around that, but we’re all in it together, so just stay tuned into the world around you and do as much as you can do. And don’t let anyone say it’s not enough. Just push yourself to do something.” Just before I managed to courteously yank myself away from such a long and thoughtful conversation, we discussed how their music has a tone that can perhaps guide the listener in difficult times. Frankel responded, “It certainly guides us through difficult times.” James agreed with a quiet “Hell yeah.”

Article: Olivia Isenhart

Photos: Shayne Hanley