“We’ll play some holiday songs, but not a whole show of holiday songs — we’re not monsters!” Rhett Miller, lead singer of the Old 97’s, joked at the beginning of the night. New York City’s Irving Plaza was the second-to-last stop of this leg of the Holiday Extravaganza tour, and the stage was festooned with strands of lights while an inflatable trio of Santa, a Christmas tree, and Rudolph — or is it Rudolphina? more on that later — kept watch over the proceedings. This festive cheer was balm in a wearying year, as was the optimism inherent in a thousand people gathering to hear their favorite band (in “A Brief for the Defense,” poet Jack Gilbert wrote that “we must admit there will be music despite everything”).

Miller, looking debonair in a dark blue velvet blazer, has been doing double-duty on this tour, opening solo and headlining with his band. For many in the crowd, it was our first chance to hear material from his eighth solo album, The Messenger, as well as the Old 97’s Love the Holidays — an assortment of original and classic Christmas songs. These two records, released in early and mid-November, are illustrative of the breadth of Miller’s work — there’s the reckoning with weighty subjects in the former and the playful spins on Christmas stories in the latter (“Rudolph Was Blue” imagines the reindeer’s search for a mate who turns out to be felicitously named Rudolphina).

The twelve-track Messenger pulses with honesty and energy — the arrangements have a lively, appealing looseness (bassist Brian Betancourt hadn’t played before with drummer Ray Rizzo, and Miller made a conscious decision to “set up and just record live off the floor really quickly”). The sonics are an effective counterpoint to the introspective lyrical arc that reckons with faults and fears. Rizzo’s drumwork is sprightly and propulsive, and Sam Cohen — who produced Benjamin Booker’s Witness and collaborates with a roster that includes Bob Weir, Norah Jones, and Joseph Arthur — adds judicious amounts of reverb-laden guitars along with bright keys and gossamer strands of pedal steel. Miller’s turns of phrase in these songs are clever (the human condition is incurable) and sometimes cutting — in “Permanent Damage,” he sings: nobody wants to hear about my stupid dream — a sentiment that feels like a wink and nod to a line from “Longer Than We’ve Been Alive,” off 2014’s Most Messed Up (I’m not crazy about songs that get self-referential). That isn’t the only lyrical Easter egg for Old 97’s devotees — the catchy (and devastatingly forthright) opening track, “Total Disaster,” includes a line about street name and the phase of the moon — likely a reference to “Oppenheimer” from 1999’s Fight Songs. All told, The Messenger feels like a series of postcards from singer to listener, reflecting the sobering truths learned as we get older, while retaining verve and drive, undiminished by the accumulation of time.

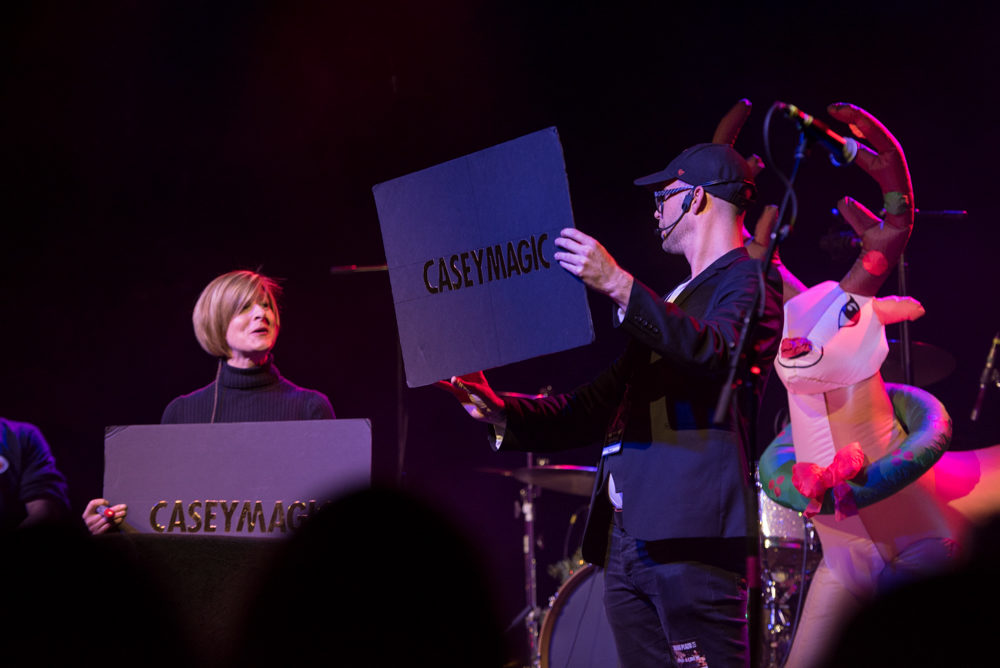

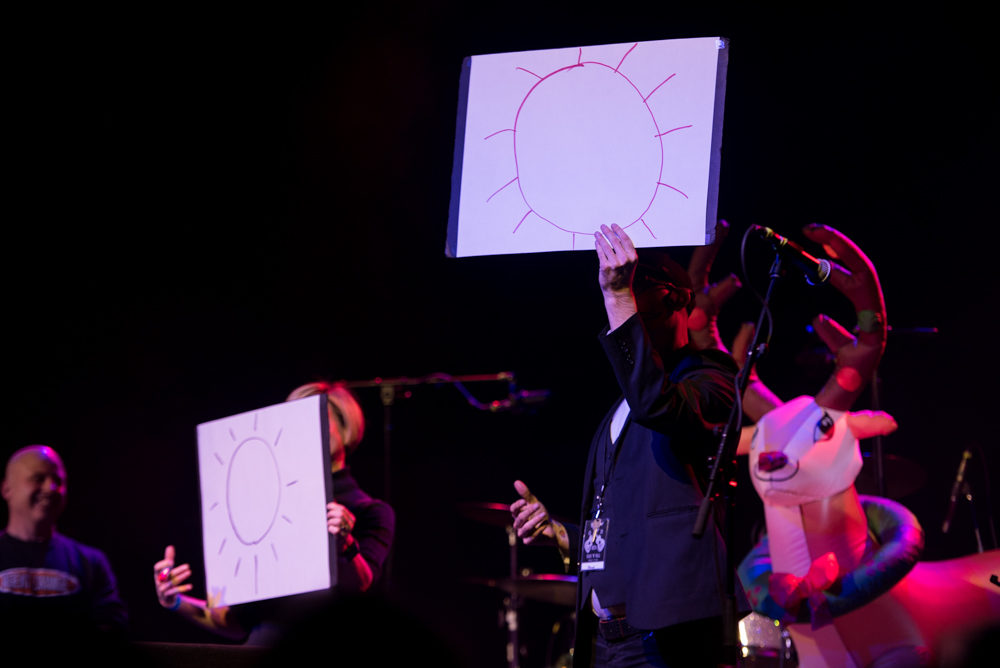

It wouldn’t be an Old 97’s holiday gathering without the delightfully unexpected, and on this tour, that came in the form of DIY punk rock magician Casey Magic. Michael Casey kept us engaged with a fast-paced series of tricks. When he placed a metal spike in one of four identical paper bags (which an audience member then shuffled around), and proceeded to smash his palm down on the empty ones — despite knowing this is all sleight of hand, I was half-convinced he was going to impale himself — a sort of stigmata. That, and the knife-throwing trick — hardcore. (As an aside, Casey’s sweetheart is Lydia Loveless, who has toured with the Old 97’s and who gifted to Rhett her bright blue Rickenbacker.)

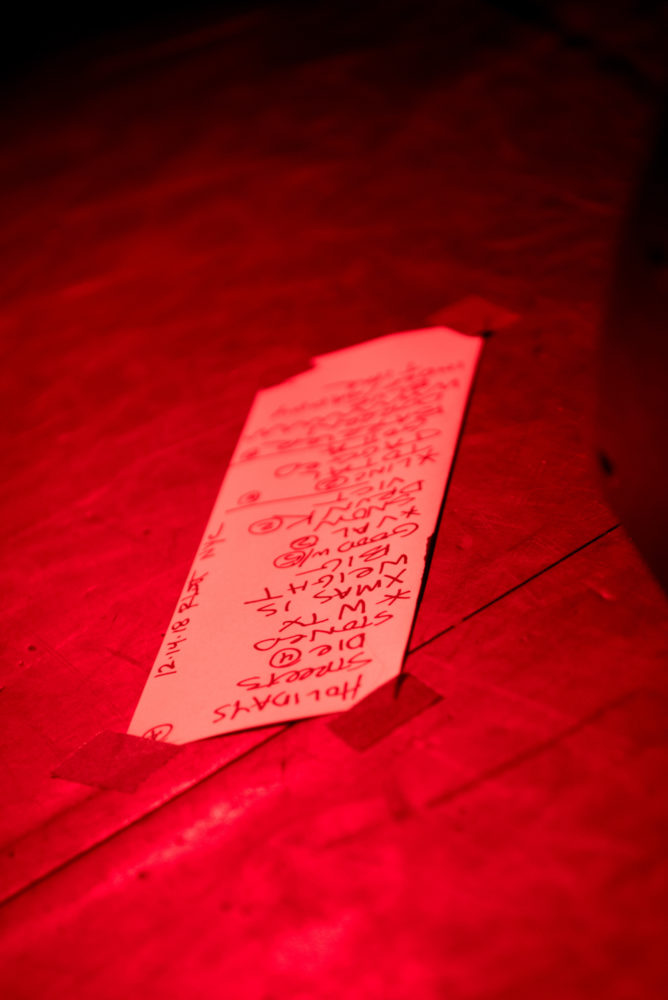

The Old 97’s took the stage to a whole lot of hollering and hooting from the packed Irving Plaza. What followed is familiar, though no less thrilling, to longtime fans. The band blazed through a career-spanning set, adding holiday songs (both off the band’s new album and a cover of “Blue Christmas”) and a Buzzcocks cover (“Everybody’s Happy Nowadays”) in tribute to Pete Shelley, who passed earlier this month.

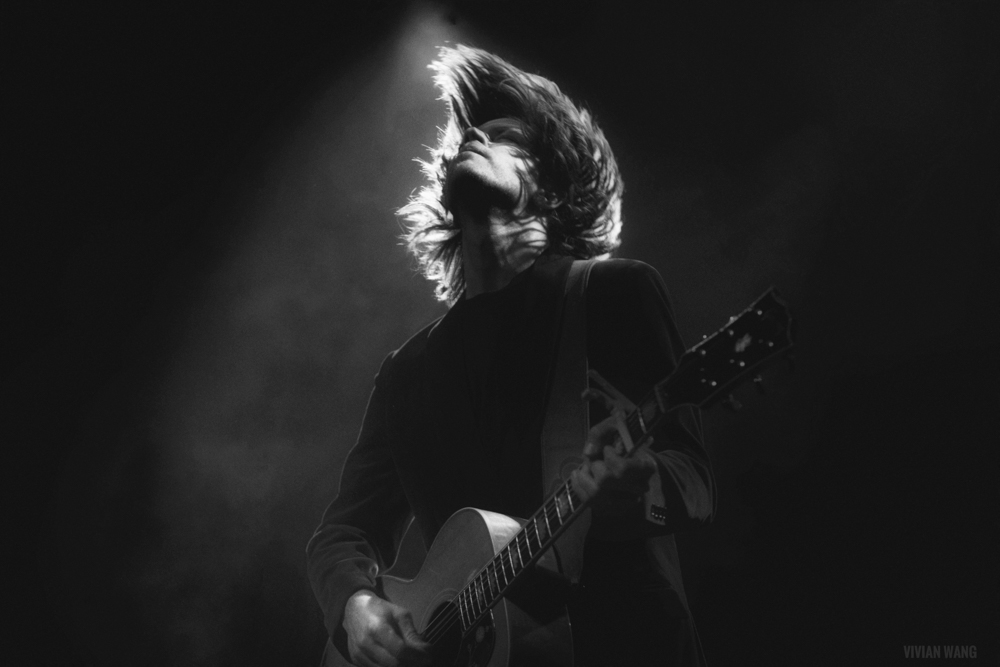

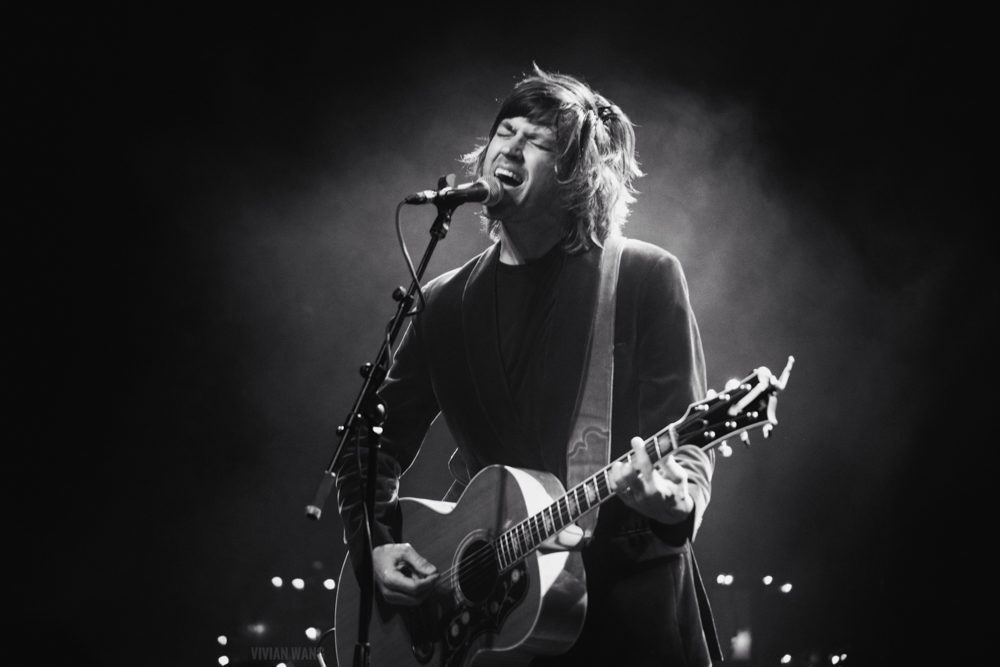

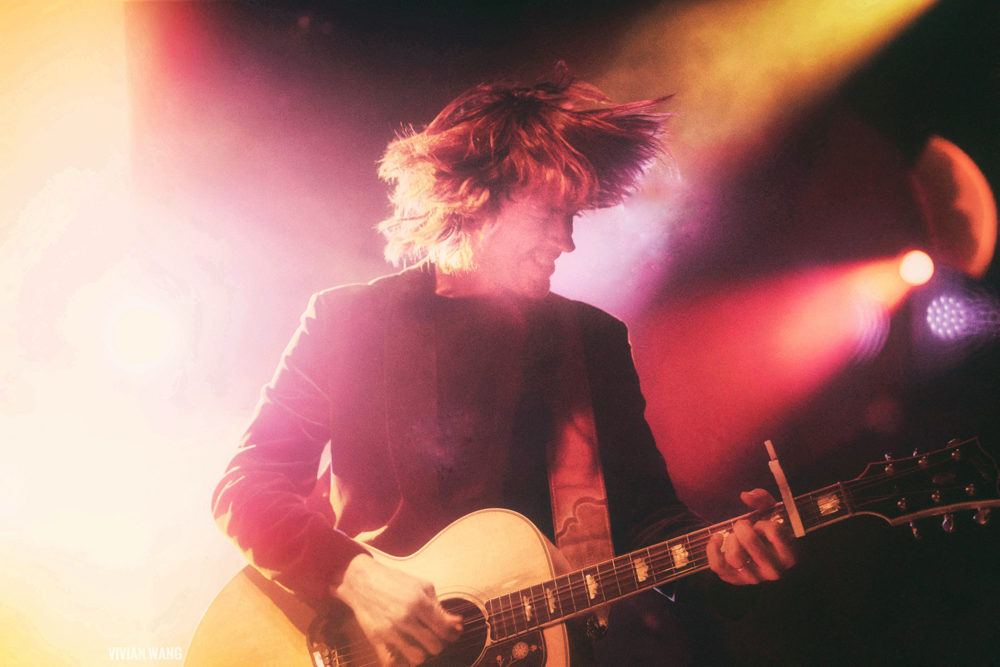

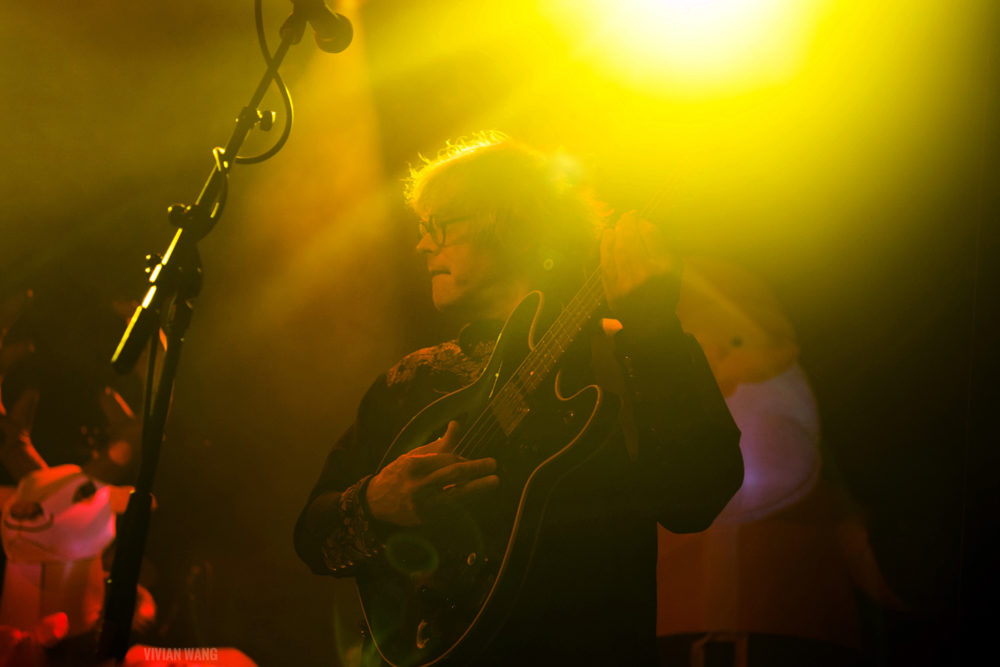

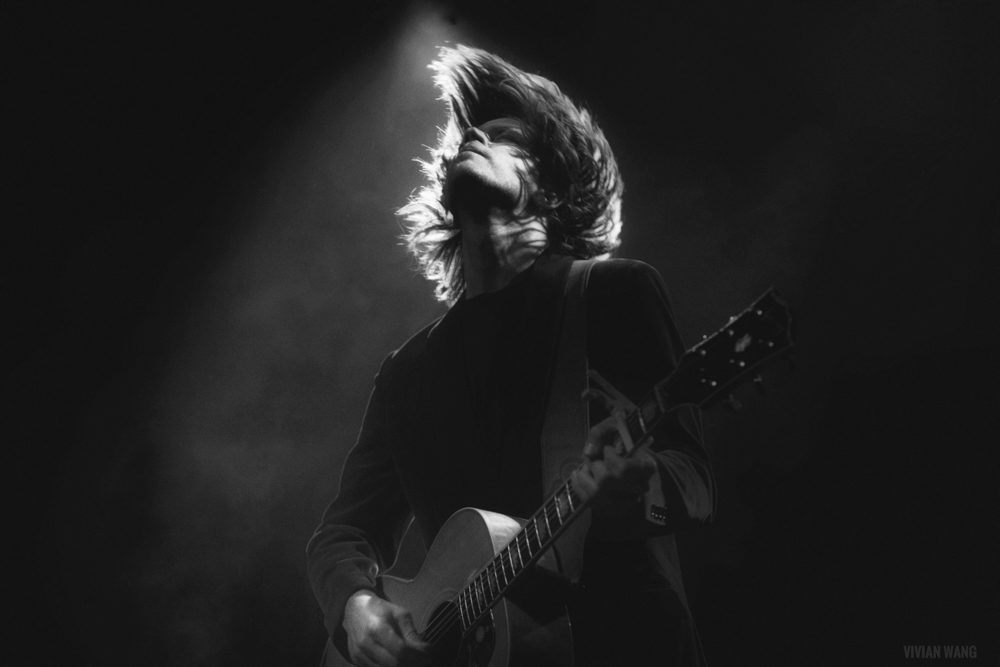

Miller’s windmill-strumming; the way Ken Bethea leans into the crowd and sticks his tongue out in playful ebullience; how Murry Hammond hoists his bass, shotgun-style, those long, denim-clad legs akimbo; and Philip Peeples’ smiles and snarls (give me a long lens and I’ll just make freeze-frames of drummer faces all night long) — all these things, you can picture from years of seeing these shows. That amalgam of punk and twang, the raucous songs about Irish whiskey and trying to land a pickup line in a Chicago bar, about God being a woman (Miller gave a shout-out to Brandi Carlile, who contributed vocals to “Good With God” from Graveyard Whistling) — all these lyrics, you’ve memorized. But we never tire of this joy, this energy, the downright adorable goofiness of these guys’ interactions on stage — twenty-five years and counting. This is a band whose albums and shows we’re lucky to have as a musical signposts through our years.

A photographer pal once remarked that photography is less about images and more about relationships — photographer/subject, subject/audience, photographer/camera. I think that’s right. When done right, photography is about more than just stopping motion for a moment — it’s about making that moment mean something. For seasoned bands like the Old 97’s, I reckon we photographers scurrying about the pit are essentially invisible — part of an ever-changing cast from city to city, with faces half-hidden behind lenses. But sometimes there’s eye contact, a small smile, the step into the frame rather than the turn away from it. Sometimes I’m able to anticipate the way a song inhabits a body — the tilt of the head, the lean into the microphone — and there’s a fraction of a second of stillness before the sound comes into being, when I know to release the shutter. These moments feel alive to me — and they make me feel alive.

These are the moments that remind me why I do this, why many of us toil (mostly in obscurity) to make pictures (that if we’re lucky, you won’t scroll right past). It’s as much documentation as it is co-creation. This is my love for these bands, as best as I can express it. I want this moment in this song to live forever, to preserve within the four corners of an image all the vitality, the passion, the connectedness. I want you, my fellow fans, to feel (not just see, but feel) these beautiful creatures, all fluidity and power on stage. And I want to communicate the flip side as well — to remind us that what brings us joy comes at a price. I think that’s why I gravitate toward the moments when, whether by positioning or lighting, the subject seems isolated on stage, alone and apart from bandmates and audience. It’s because of what I see (and imagine) when the venue empties out — what happens when the adrenaline wears off and the weariness sets in. There’s the restless early mornings, tossing and turning on a couch (or, if you’re relatively lucky, a bunk on the tour bus). Always traveling, each arrival soon turning into a departure, with not enough alcohol to dull the anxiety but too much alcohol to be offset by gas-station coffee. I fear there’s an upper limit to the cycles of regeneration for the phoenixes we see burning bright under stage lights. And (less importantly, more selfishly) I fear there’s a point at which the way photography and writing make me feel present, connected — will not be enough.

None of that is entirely in my control (if at all). But after we lost Frightened Rabbit’s Scott Hutchison in May, I’m trying to be better about not leaving things unsaid, even if they seem obvious. So to the Old 97’s ruffians (musicians and crew, both) — you are so loved for who you are and what you create, both in song and in community. To the editors and publicists who give me free rein to photograph and write what I want — I appreciate your trust. To my friends in the NYC music world — the denizens of Berlin, Bowery Electric, and Coney Island Baby who give me opportunities to document rock ‘n roll in all its gritty glory — I couldn’t keep at this without your support. And to fellow music fans who know what it means to hold onto songs like lifelines, and who take time to read these pieces — thank you for your encouragement and for making this community vibrant (but maybe find a better use for your time than reading my essays, ‘cos I’m not particularly skilled at this).

It’s been a hard year, both because of the deeply troubled state of the union and because that inner darkness — the stuff of Frightened Rabbit songs, the hard truths behind the beautifully poignant tracks from The Messenger (and 2017’s Graveyard Whistling) — is so dense that some days, I can hardly see through it. So I try to take my cue from friends in the NYC music scene, and from Miller, who said in a recent Rolling Stone interview that the act of creation is what gets him out of the darkest places.

I reckon I’ll try to do the same — to document and create in the hopes that “we’ll be together, long as the wheels go ’round.”

Happy holidays, friends. Chin up. Steady on. And pick up The Messenger here, and Love the Holidays here.

Article: Vivian Wang